About those Disney notices ...

Public Notice Resource Center & NNA

May 1, 2023

You might have heard that the Walt Disney Co. recently took steps to frustrate Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ attempt to strip the entertainment conglomerate of its power to appoint members of the board that provides oversight for Disney World.

According to a story published late March in the New York Times, the Disney-appointed Reedy Creek Improvement District (RCID) Board of Supervisors “quietly pushed through a development agreement” preventing the governor from replacing them with his allies, thereby maintaining Disney’s governance of the world’s largest theme park. The Board proposed the agreement at a public meeting on Jan. 25 and approved it at a follow-up meeting on Feb. 8.

The Times wasn’t the only news organization that framed Disney’s maneuver as a secretive procedure. That was the general tenor of the news coverage surrounding the story.

It’s undeniable that Disney and its chosen representatives on the RCID Board hoped their maneuver would evade detection. Reedy Creek was established in 1967 by the Florida legislature with the Board serving as the governing body for the special district. Like all governing bodies, it prefers to control the flow of information to the public.

But Florida’s public notice laws made it difficult for them to do that.

Title XI, Chapter 163, Section 3225 of the state’s statutory code requires local governments — including special districts — to “conduct at least two public hearings” to create or change a development agreement. It also requires them to provide “(n)otice of (their) intent to consider a development agreement” by advertising each hearing “in a newspaper of general circulation and readership in the county where the local government is located.” Reedy Creek straddles both Orange and Osceola Counties in east central Florida.

As the Times noted in its reporting, Disney provided such notice with ads published in the Orlando Sentinel. Both notices were also posted on the Sentinel’s website and the Florida Press Association’s statewide public notice site, a fact the Times appeared to be unaware of.

That means the ads were published in a newspaper delivered to over 50,000 print and digital subscribers in the area, and they were posted on websites that collectively generate over 3 million monthly visits, according to the website traffic comparison site Similarweb.com (https://www.similarweb.com/). Moreover, the Sentinel’s website is the most-visited local news site in the Orlando area, according to Scarborough Research.

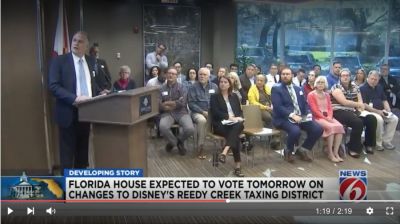

As far as we can tell, the ads worked. Although the Board appears to hold its meetings in a relatively small room, news footage from the Feb. 8 hearing, at which the development agreement was approved, suggests it attracted a standing-room only crowd. (See screenshot above. WKMG News 6 later noted “several dozen spectators” attended the meeting — https://bit.ly/3mNCGtK) There were also reporters and news cameras in the room.

So this was no secret deal cut in the middle of the night. It was approved during the course of two properly noticed public meetings that many people attended. But not a single news organization that originally covered the meetings reported on the significance of the agreement. In fact, the Sentinel appears to be the only local outlet that even mentioned that the Board discussed a development agreement.

Why didn’t anyone in the packed room figure out what Disney was up to? Because they would have had to pick up a copy of the development agreement at RCID’s office, and then read and appreciate the significance of the agreement — a legal document contained within an imposing 151-page paper festooned with maps, budgets, construction schedules and impenetrable legal descriptions of real property.

Florida’s public notice law required Disney’s RCID Board to make that document available to the public. But it didn’t require them to stand on a table at the meeting and shout, “Hey DeSantis, we’re going woke and there’s nothing you can do to stop us!”

The only people in the state who might have uncovered Disney’s plan were a relatively small universe of those with a professional interest in the future of Disney World and the expertise to recognize the impact of the development agreement. Most of the members of that cohort either work for or are allied with the DeSantis administration or Florida’s GOP legislative caucus.

“Disney didn’t do anything secret. They publicized (their plan); they advertised it,” former Florida Republican legislator and law school teacher Juan-Carlos Planas told the Wall Street Journal. “If you’re in Tallahassee, and you’re replacing the board, how do you not know what that board is doing in their public meeting? This was negligence on the part of the governor’s office and Republican legislators.”

Nevertheless, Gov. DeSantis sent a letter asking Florida’s Chief Inspector General to investigate the RCID Board’s actions, claiming that among other “legal infirmities” it might have provided “inadequate notice.”

It’s worth noting that under the new law passed last year that made Florida the first state in the U.S. to allow local governments to publish notices on county government websites in lieu of publication in print newspapers and newspaper websites, Disney and the RCID Board will have even more power to conceal their plans from the public.

Think it’s difficult to parse Disney's intentions now? Wait to see how much they can hide when they’re allowed to move all their planning to the Orange County and Osceola County websites. According to Similarweb, those sites collectively serve about 10% of the number of readers who regularly visit the Orlando Sentinel’s website.