Saving 2 small-town newspapers

May 1, 2020

These South Dakota newspapers — The De Smet News and The Lake Preston Times — have a combined weekly circulation of about 1,900

On April 1, Dale Blegen, the longtime owner and publisher of the papers, announced that he was calling it quits and closing the papers with the headline, “This is it!”

Blegen had hoped to retire at 65 but was still at it 10 years later. Unable to sell the papers, he just kept going to serve his communities. But he felt the COVID-19 crisis was the last straw.

The papers were profitable, but any significant drop in advertising meant he would be operating at a loss and running up debt. After 45 years and more than 2,200 editions of the News and 1,800 editions of the Times, Blegen felt it was time to call it.

In the Arlington Sun, the county’s only other newspaper, Frank Crisler wrote that it was impractical for the Sun to cover the towns of De Smet and Lake Preston. He, like others, hoped a white knight might swoop in to save the papers, but he admitted it was unlikely.

“The sun will come up tomorrow in Lake Preston, and a few seconds later, in De Smet. But for the first time in 140 years, there will be no newspapers there,” he wrote. “That’s nothing but sad.”

The community was stunned by the April 1 announcement. They had no warning. The papers were the oldest institutions in their communities. And suddenly, the residents realized that their communities just weren’t the same.

The De Smet Development Corporation took up the issue and started researching some options.

Sadly, this is a common problem — especially in rural areas — as 1,800 papers have folded, 20% in the past dozen years or so. There are news deserts spreading across America as towns and communities lose their local papers.

As the De Smet development board dug deeper to put together a plan to rescue the papers, the group realized that publishing a newspaper was a pretty significant undertaking.

They calculated that it takes about 250 hours every week to report, sell, produce and print the local papers, which only averaged about eight pages each.

“We had no idea,” said Tim Aughenbaugh, a member of the development board. “We had never thought about what went into our local paper. A lot of us were amazed at what a treadmill running a weekly paper can be. That was a revelation.”

The team started investigating different parts of the puzzle. They talked to the paper’s printer and other publishers in South Dakota. They reached out to the press association for information. They searched the internet for examples of communities saving their newspapers.

While many residents were willing to help and were very supportive, they couldn’t find many examples of communities saving their papers. But they did find one, and it proved to be an inspiration for the plan the communities have laid out to save their papers.

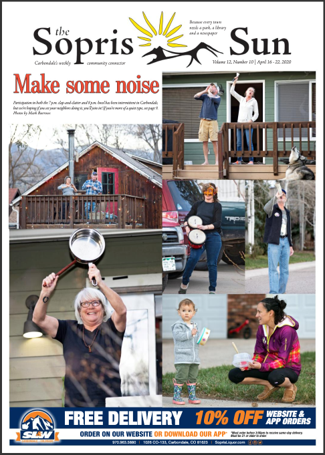

Aughenbaugh came across an article in the Los Angeles Times about a small paper in Carbondale, Colorado. When that paper, the Carbondale Valley Journal, folded, the community banded together to start a new paper. They called it the The Sopris Sun, which is a nonprofit staffed mostly by volunteers.

The economics, size and scale of their startup was very similar to what the two local newspapers were facing. So, the group set out to see if they could make the economics of that model work for their communities in South Dakota.

Aughenbaugh’s internet search also led him to Bill Ostendorf, president of Creative Circle Media Solutions in East Providence, Rhode Island.

Creative Circle works mostly with smaller, family owned newspaper companies, and Ostendorf helped community leaders in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, when they bought their local daily and three Vermont weeklies away from a hedge-fund-backed chain.

The Massachusetts leaders were frustrated by watching the dramatic decline in The Berkshire Eagle after the corporate purchase, and they wanted to restore the paper to the top-notch local publication it had been under local ownership. Creative Circle redesigned the paper, advised the ownership group, and provided web hosting, design and software.

Aughenbaugh thought Creative Circle’s software and expertise could help the small South Dakota towns, too. And Ostendorf was receptive to the cause.

“I hate to see any loss of locally produced newspapers,” Ostendorf said. “I really believe that newspapers should be locally owned or family owned because newspapers need owners who give a damn about their communities.”

Ostendorf had also been actively seeking funding to fill in rural news deserts by building websites for some of America’s smallest papers — many of which had never had a website before.

“We estimate there are roughly 200 small, rural newspapers like these that have never had a website, and we’ve been seeking funding for a plan to offer free websites to these papers — along with appropriate training — to help them survive and give them the option to go digital rather than close down.”

Ostendorf offered to help in any way he could — building websites, redesigning the papers, training the staff or even producing the papers for a few weeks, if necessary. While he couldn’t completely donate his company’s efforts, he was willing to do whatever it took now and worry about getting paid sometime later. He also said he’d do the work for whatever the communities could afford.

But Ostendorf was blunt about how difficult this would be — training a bunch of volunteers to put out a newspaper was no simple task. Another problem that the team faced was that they had a deadline. The papers had to publish again by May 13 or risk losing their postal permit and critical legal advertising. May 13 was about three weeks from Aughenbaugh’s first call to Creative Circle.

But now they had pieces they could put together with a plan and maybe, just maybe, save the papers.

The De Smet Development Corporation reached out to the Lake Preston Development Corporation, and the two groups purchased the papers and their facilities. After leading town meetings to explain the plan to their communities, initial volunteers began to step forward. The plan included setting up each paper as a community organization to benefit the communities.

While the papers would start off with volunteers, the goal would be to pay those volunteers a percentage of any profit — hopefully reaching the point where the volunteers would be fully paid.

Since the papers were profitable before the COVID-19 crisis, if payroll became an option — not an obligation — the groups felt the model could work.

Ostendorf’s team at Creative Circle is redesigning the papers with an eye toward making production easier and faster. One paper was a broadsheet, while the other was a tab. After the redesign, both paper will be tabs and can share content or advertising. The redesign will also simplify layout and provide lots of stylesheets and templates. Creative Circle will produce the first issue entirely, taking the next 3-5 weeks to gradually shift production back to the volunteer team.

Creative Circle will provide volunteers with training involving everything from writing interesting stories and headlines to taking better pictures, in addition to InDesign and layout training.

Meanwhile, Creative Circle will launch websites for both papers that will allow community members to contribute content. The websites will take classified ads online, provide the circulation database and payment system, and provide an archive for future editorial content.

With the redesign and new technology provided by Creative Circle, the group hopes to reduce the estimated 250 hours needed to produce the papers each week by 30%. The websites should also generate some additional revenue.

“With some publicity, I’m hoping the teams in De Smet and Lake Preston can get some more help with a grant, some volunteers or even an editor who might want to take on this challenge,” Ostendorf said. “And I’m thrilled to help any community take back its newspaper. This is the future of newspapers. These big, venture groups who own most newspapers in America now will eventually fall apart, and communities will need to rise up and pick up the pieces. I want to help develop models that will allow newspapers to return to local ownership.”

Aughenbaugh said, “We’ve ended up with so many talented people who have stepped up to help us — here in our community, from the South Dakota Newspaper Association, our printer and Creative Circle.” Members of both development boards and their local attorney/board member Todd Wilkinson have all also stepped up to help make this happen.

And Aughenbaugh can’t say enough good things about Dale Blegen, the former owner. “He served these communities for 43 years and was only the third publisher of the papers, which date back to 1885,” he said. “Every birth. Every wedding. Every death. Every win. Every loss. If he and his employees had not been here, there would have been no record of any of it.”

“It has taken a team effort to get us to the point where we have a believable plan,” Aughenbaugh said. “But that plan needs to be executed, and it is only going to be successful if both of our communities get behind it.

He continued, “I’m optimistic. I don’t underestimate the challenges we have here. But we don’t see another way to do this. If we don’t figure this out, there will be no record of our lives or our communities.

While people who work at newspapers are always rooted in the present — in getting out this week’s paper — “the reason for communities like ours to have a paper is really for the future,” Aughenbaugh said. “Making our communities better. Engaging people in discussions. Without the paper getting people involved now in helping us think about our future, every plan and every effort is just scattered. It’s the paper that brings focus and brings people together and makes the community better.

“But there is also a bigger cause here that’s worthy,” Aughenbaugh said. “Communities like ours need our newspapers.”